When should I worry about my child’s height?

Dr. Hesham Farouk

Specialist Pediatrician

Aster Discovery Gardens & Arabian Ranches

At every well-child visit, newborn through adolescence, your pediatrician will measure your child’s height. In part this is because growth is a measure of health and well-being, but your doctor will also be tracking the rate at which your child is growing toward his or her estimated target height. This is calculated with a standardized formula so doctors have an objective measure to identify potential growth problems, called short stature.

Short stature

is a term applied to a child whose height is 2 standard deviations (SD) or more below the mean for children of that sex and chronologic age (and ideally of the same racial-ethnic group). This corresponds to a height that is below the 2.3rd percentile. Short stature may be either a variant of normal growth or caused by a disease.

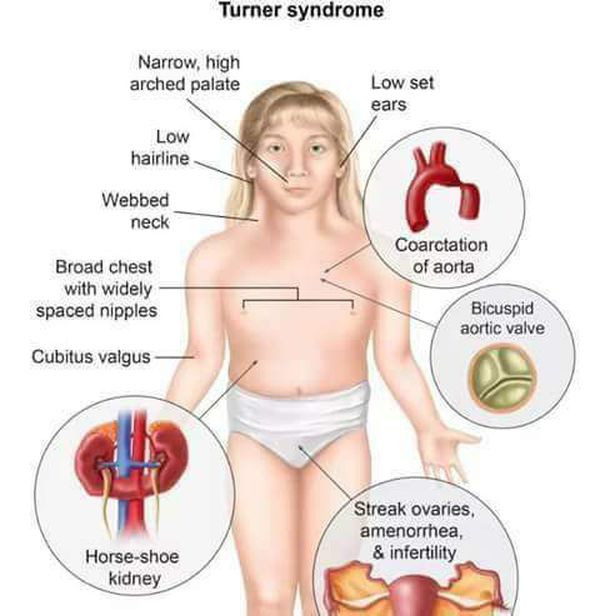

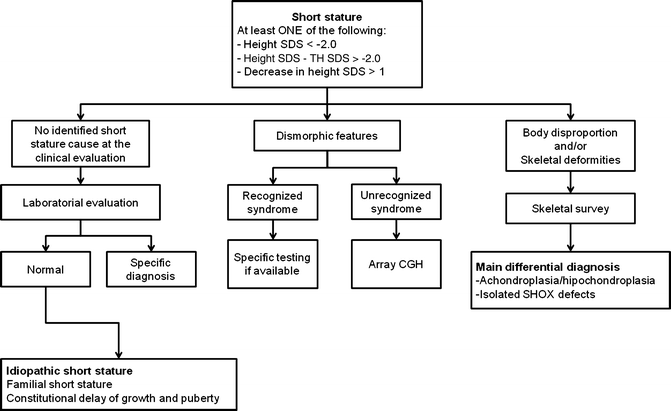

The most common causes of short stature beyond the first year or two of life are familial (genetic) short stature and delayed (constitutional) growth, which are normal, nonpathologic variants of growth. The goal of the evaluation of a child with short stature is to identify the subset of children with pathologic causes (such as Turner syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease or other underlying systemic disease, or growth hormone deficiency). The evaluation also assesses the severity of the short stature and likely growth trajectory, to facilitate decisions about intervention, if appropriate.

How to determine if growth is normal

- Physiology of Growth

Hormonal regulation of human growth involves the growth hormone (GH)-insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) axis. There is also clearly a genetic contribution to human growth. This is discussed further under normal (parental growth and development history) and abnormal growth patterns (Turner syndrome and SHOX deficiency). GH is important in promoting somatic growth and in regulating body composition and muscle and bone metabolism. Some of these GH effects are direct actions whereas others, specifically linear growth, are mediated through IGF-I.

-

The original “somatomedin (alternatively termed IGF) hypothesis” postulated that somatic growth was controlled by pituitary GH and mediated by circulating IGF-I produced exclusively by the liver. The discovery in the late 1980’s that most tissues produce IGF-I, supporting a role of autocrine/paracrine IGF-I, led investigators to modify the original hypothesis to what is known today as the “dual effector” theory. Experiments using gene deletions and transgenic technologies have revealed new information that again has led investigators to revisit the hypothesis. These experimental studies in mice have shown that, while the liver is the principal source of IGF-I in the circulation, hepatic IGF-I is not required for postnatal growth. Extrapolating to humans, this finding indicates that autocrine/paracrine (local) IGF-I produced in cartilage itself, but not liver-derived (endocrine) IGF-I, may be the major determinant of postnatal somatic growth.

Growth Velocity

A newborn’s size is determined by its intra-uterine environment, which is influenced by maternal size, nutrition, general health, and social habits, such as smoking or drinking alcohol. Thus, an “overnourished” mother can have a heavier and longer baby and an “undernourished” mother can have a lighter and shorter baby than otherwise dictated by family growth genetics. The average weight of a newborn is 3.25 kilograms (7.25 pounds) and the average length is 50 centimeters (19.7 inches). After birth, the linear growth rate becomes more dependent on the infant’s genetic background.

Important physiological phenomena, known as catch-up and catch-down growth, occur in the first 18 months of life. In two-thirds of children, the growth rate percentile shifts after birth until the child reaches his or her genetically determined height percentile.

Some children (born too small because of uterine fetal constraint) move upward (catch-up) on the growth chart because they have tall parents, whereas others (oversized at birth because of excessive maternal nutrition during the pregnancy) move downward (catch-down) on the growth chart because they have short parents. By 18 to 24 months of age, most children’s stature has shifted to their genetically determined percentiles. Thereafter, growth typically proceeds along the same percentile until the onset of puberty

Genetic Potential

Determination of the MPTH is a critical first step in the assessment of a child’s stature, and obtaining accurate parental height measurements is essential when determining the MPTH. A large proportion of parents who bring their children for a consultation with a pediatric endocrinologist make a significant error in reporting their own heights. Since parental height often determines the extent of a work-up and/or therapeutic intervention, it is the opinion of the authors that parents’ heights should be directly measured whenever possible.

The MPTH is a child’s projected adult height based on the heights of his or her parents. Sex-specific calculations are shown in Table 2. For both genders, 1.7 inches on either side of the calculated MPTH is ~1 SD while 3.3 inches on either side is ~2 SD. By calculating the percentile and range for the MPTH, it can be determined if a child is growing on a percentile that is within or outside this range.

Mid-Parental Target Height Formulas:

Boys: [father’s height in inches + (mother’s height in inches + 5 inches)]/2

Girls: [(father’s height in inches- 5 inches) + mother’s height in inches]/2

Fast facts on short stature

Here are some key points about short stature. More detail is in the main article.

-

Short stature can happen for a wide range of reasons, including having small parents, malnutrition and genetic conditions such as achondroplasia.

-

Proportionate short stature (PSS) is when the person is small, but all the parts are in the usual proportions. In disproportionate short stature (DSS), the limbs may be small compared with the trunk.

-

If short stature results from a growth hormone (GH) deficiency, GH treatment can often boost growth.

-

Some people may experience long-term medical complications, but intelligence is not usually affected.

Etiology

Stature is a hereditary trait and controlled by both genetic as well as environmental factors.

Short stature is caused by four major reasons.

-

Genetics: The height of a person is determined by their genetic makeup. If any of the parents have short stature or recorded it in their family history, then there is a greater possibility that the person also has short stature. But, genetic short stature is applicable only if there is no underlying medical reason. This has also been categorized as familial short stature (FSS). Individuals having the genetic makeup of short stature will reach the height within the target height range. They have a normal growth rate and have no bone age delay.

-

Constitutional growth delay: Constitutional growth delay deals with the tempo of growth or growth velocity. The tempo of growth throughout the growth process of these individuals may be slow or normal. Some children develop later than others, i.e., they have delayed bone age. They are small for their age and enter puberty at later ages than others. However, they usually catch up at adulthood, having short stature during their childhood but the relatively normal height at adulthood. The reasons for this may include malnutrition during the gestational period, and early childhood or could be genetic. Malnutrition is one of the factors affecting the tempo of growth and bone development, which may further aggravate short stature in a genetically predisposed individual. Malnutrition during the gestational period results in underweight infants, whereas, during childhood, it causes stunted growth. Along with malnutrition, genetics play a crucial role in determining the tempo of growth. These individuals may be categorized into the constitutional delay of growth and adolescence (CDGA)

-

Early puberty: Short stature may also be caused due to precocious puberty of the child. Due to early puberty, the growth potential of a child may not be completely realized. There are various reasons behind the attainment of early puberty, including earlier development of ovaries, adrenals, and pituitary, cerebral and central nervous system abnormalities, as well the family history of the disease, showing a genetic nature.4.

-

Medical reasons: There are a number of medical reasons that cause short stature. These include diseases and disorders, the most significant being hormonal deficiencies:

-

Endocrine disorder: The major medical cause of short stature is the growth hormone deficiency (GHD). This may be categorized as an endocrine disorder. Human growth is regulated by the growth hormones. The growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) released by the hypothalamus stimulates the production and secretion of growth hormone (GH) from the anterior pituitary. These growth hormones act on the liver and other tissue and stimulate the secretion of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), which further acts on the bones and promotes endochondral ossification. Pagani et al. (2017), found a positive correlation between IGF-1 and stature, demonstrating lower levels of IGF-1 in individuals with short stature. Another endocrine cause for short stature is the deficiency of androgen, causing decreased bone formation and development.

-

Genetic disorders: There are various genetic disorders that affect growth, including Down syndrome, Turner syndrome, 3M syndrome, Noonan syndrome, Prader-Willi syndrome, Aarskog syndrome, Silver-Russell syndrome, short stature homeobox gene deficiency, etc. These genetic disorders affect the growth of an individual, resulting in short stature. They are also associated with hormonal imbalances, which may manifest as ovarian insufficiency, slowed growth, lack of growth spurts at expected times, irregular menstrual cycles, etc.

-

-

Bone diseases: Bone diseases affect bone growth, thus affecting the stature of the person. These diseases include achondroplasia (short-limbed dwarfism), diastrophic dysplasia (short-limbed dwarfism), spondyloepiphyseal dysplasias (short-trunk dwarfism), rickets, etc.

-

Chronic disorders: Chronic disorders also affect the overall growth of a person, including stature. These disorders include cystic fibrosis, Crohn diseases, juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), anemia, chronic renal insufficiency, inflammatory bowel disorder, etc.

-

-

-

-

Environmental pollutants: Studies have shown that exposure to environmental pollutants such as lead, cadmium, hexachlorobenzene (HCB), polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB), etc., have been associated with reduced height

What tests might be used to assess your child:

-

The best “test” is to monitor your child’s growth over time using the

growth chart.

Six months is a typical time frame for older children; if

your child’s growth rate is clearly normal, no additional testing may be

needed.

In addition, your child’s doctor may check your child’s bone age

(radiograph of left hand and wrist) to help predict how tall your child will

be as an adult.

Blood tests are rarely helpful in a mildly short but healthy

child who is growing at a normal growth rate, such as a child growing

along the fifth percentile line. However, if your child is below the third

percentile line or is growing more slowly than normal, your child’s doctor

will usually perform some blood tests to look for signs of one or more of

the medical conditions described previously.

Diagnostic Tests and Interpretation

- Test: Radiograph of the left hand and wrist

- Significance: BA determination (not reliable in kids <2 years of age)

- Test: IgA and anti-tissue transglutaminase IgA

- Significance: celiac disease

- Test: CBC with differential

- Significance: anemia, infection, malignancy, or chronic inflammatory conditions

- Test: C-reactive protein (CRP) and/or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

- Significance: infection, inflammatory conditions

- Test: complete metabolic panel

- Significance: renal/liver disorders, malnutrition, calcium disorders

- Test: urinalysis

- Significance: diabetes, renal/metabolic issue

- Test: T4/free T4 and TSH

- Significance: hypothyroidism

- Test: karyotype or targeted gene testing

- Significance: Turner syndrome in girls, SHOX mutation, or other chromosomal disorders

- Test: IGF-1 and Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 (IGF-BP3) concentrations, compared to pubertally matched norms

- Significance: proxy measurements for GH secretory reserve and screen for GH deficiency; not reliable <3 years of age and IGF-1 can be falsely low in poor nutrition states

The proper evaluation of short stature is conducted in an outpatient setting with a calibrated stadiometer. The most useful information in the evaluation of a child with short stature is the child’s growth pattern

Management

-

General Measures

Evaluation warranted if HV low for age or growth pattern deviates significantly from the MPH target.

-

In the majority of short children, history and exam are unrevealing, and tests yield equivocal or normal results. These children are then considered to have idiopathic short stature.

-

Observation is reasonable for familial short stature or constitutional delay.

-

In cases of malnutrition, restoration of adequate nutrition results in HV acceleration.

-

In cases of endocrinopathies, replacement of the deficient hormone (thyroid hormone for hypothyroidism, GH for GH deficiency, hydrocortisone for adrenal insufficiency) or removal of excess hormone (glucocorticoids) will normalize the HV.

-

Children with short stature or poor predicted adult height, who do not have true GH deficiency, may receive different evaluation and treatment options depending on costs, risks, physician practice, extent of family’s concern, and presence of associated psychosocial stressors (e.g., teasing by peers).

Issue for Referral

-

Critical to obtain accurate measurements plotted appropriately to assess growth

-

Referrals should be guided by abnormal laboratory evaluations or clinical suspicion (i.e., nephrology referral for elevated creatinine, pulmonary referral for clubbing).

-

Endocrine referral warranted if slow HV, growth plateau, delayed bone age with short stature/ growth failure, or suggestive labs.

-

If poor weight gain, consider nutritional deficiency, malabsorption syndromes; initial referral to gastroenterologist appropriate

-

The evaluation of growth failure or short stature best done in outpatient setting

Once referred to endocrinologists, decisions regarding treatment depend on physician and family perspectives on: 1) whether short stature is a disorder or disability warranting medical treatment and, if so; 2) whether the therapeutic goal should be faster growth during childhood or a normal, increased, or maximum attainable adult height; 3) responsible use of resources, and concerns about long-term safety.

Management options for non-GH deficient short stature

The rationale for treating childhood short stature includes increasing height and alleviating psychosocial disability while maintaining favorable risk/benefit and cost/benefit ratios. Selection among management options may therefore depend on the degree to which each meets these goals.

Surgical care depends on the underlying cause of short stature. Brain tumors that cause hyposomatotropism may require neurosurgical intervention, depending on the tumor type and location . Limb-lengthening procedures have been performed but carry enormous morbidity and mortality risks and are not recommended.

Treatment for Late Bloomers

Another treatment available is an aromatase inhibitor, which blocks the enzyme that converts testosterone into estrogen. Estrogen is what causes growth plates to close in both females and males.

We typically use this treatment in male adolescents who developed quickly and their growth plates are going to close quickly or are late bloomers who may run out of time. Again, this treatment won’t make a boy taller than he should be, but it’ll buy more time so he can grow to his full potential.

Treatment for Delayed Puberty

If a child has delayed puberty (a girl doesn’t have any sign of breast development by age 12-13 and a boy hasn’t had any sign of testicular enlargement by age 13-14) we can give the child a short (4-6 month) burst of estrogen or testosterone, which stimulates puberty and growth. A child who is simply a late bloomer will typically develop and grow in response to this treatment alone. If they respond well, then the treatment will be discontinued, and they will be followed to see how they grow.

We use cookies to provide you with the best possible user experience. By continuing to use our site, you agree to their use. Learn more